PASS Summit 2013 Keynote - Back to Basics

22 October 2013

Dr. David DeWitt recently presented a keynote (video, slides) for PASS Summit 2013 on the new Hekaton query engine. I was impressed by how the new engine design is rooted in basic engineering principles.

First Principles

Software engineers and IT staff are bound to the economics and practicalities of the computing industry. These trends define what we can reasonably do.

1: It’s About Latency

Peter Norvig, Director of Research at Google, famously wrote Numbers Every Programmer Should Know, describing the latency of different operations.

When a CPU is doing work, the job of the rest of the computer is to feed it data and instructions. Reading 1MB of data from memory is ~ 800 times faster than reading it sequentially from a disk.

A recent hype has been “in-memory” technology. These products are based on a constraint: RAM is far, far faster than the disk or network.

“In-memory” means “stored in RAM”. It’s hard to market “stored in RAM” as the new hotness when it’s been around for decades.

2: It’s About Money

The price of CPU cycles has dropped dramatically. So has the cost of basic storage and RAM.

You can buy a 10-core server with 1 terabyte of RAM for $50K. That’s cheaper than hiring a single developer or DBA. It is now cost effective to fit database workloads entirely into memory.

3: It’s About Humility

I can write code that is infinitely fast, has 0 bugs, and is infinitely scalable. How? By removing it.

The best way to make something faster is to have it do less work.

4: It’s About Physics

CPU scaling is running out of headroom. Even if Moore’s Law isn’t ending, it has transformed into something less useful. Single-threaded performance hasn’t improved in some time. The current trend is to add cores.

What software and hardware companies have done is add support for parallel and multicore programming. Unfortunately, parallel programming is notoriously difficult, and runs head-first into a painful problem:

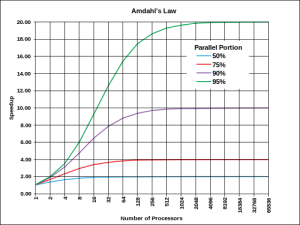

Amdahl’s Law

As the amount of parallel code increases, the serial part of the code becomes the bottleneck.

Luckily for us, truly brilliant people, like Dr. Maurice Herlihy, have invented entirely parallel architectures.

5: It’s About Quality Data

“Big Data” is all the rage nowadays. The number and quality of sensors has increased dramatically, and people are putting more of their information online. A few places have truly big data, like Facebook, Google or the NSA.

For most companies, however, the volume of quality data isn’t increasing at nearly as rapid a pace. I see this all the time; OLTP databases are growing at a much smaller pace than their associated ‘big data’ click-streams.

6: It’s About Risk

Systems are not upgraded quickly. IT professionals live with a hard truth: change brings risk. For existing systems the benefit of change must outweigh the cost.

Many NoSQL deployments are in new companies or architectures because they don’t have to migrate and re-architect an existing (and presumably working) system.

Backwards compatibility is a huge selling point. It reduces risk.

7: It’s About Overhead

Brilliant ideas don’t come from large groups. The most impressive changes come from small groups of dedicated people.

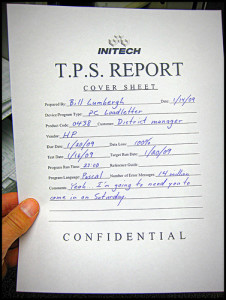

However, most companies have overhead (email, managers, PMs, accounting, etc). It is easy to destroy a team’s productivity by adding overhead.

I have been in teams where 3 weeks of design/coding/testing work required 4 **months **of planning and project approvals.

Overhead drains productive time _and _morale.

Smart companies realize this and build isolated labs:

- AT&T had Bell Labs

- Microsoft has MS Research

- Lockheed had Skunk Works

- Obama for America had its Technology team

- Facebook had its Battle Cave

The Keynote

Dr. DeWitt’s keynote covered how these basic principles contributed to the Hekaton project.

- Be Faster, Cheaper: Assume the workload is entirely in memory because RAM is cheap. Optimize data structures for random access

- Do Less Work: Reduce instructions-per-transaction using compiled procedures

- Avoid Amdahl’s Law: Avoid locks and latches using MVCC and a latch-free design. The only shared objects I could identify were the clock generator and the transaction log.

- Sell to Real People: Build it into SQL Server with backwards compatibility to encourage adoption.

- Build It Smartly: Use a small team of dedicated professionals. The Jim Gray Systems Lab has 9 staff and 7 grad students. Microsoft’s Hekaton team had 7 people. That’s it.

…Gotcha!

I have hope for the new query engine, but also concerns:

- It’s only in SQL Server Enterprise Edition (\(\)). Microsoft’s business folks clearly aren’t encouraging wide adoption of this feature.

- The list of restrictions for compiled stored procedures makes them useless without major code changes

- The new cost model and query optimizer will have bugs. It took years of revisions for the existing optimizer to stabilize.

Here Endeth the Lesson:

- Make architecture changes based on sound engineering principles**

- Assemble a small group of brilliant people, and then get out of the way.**

The Principal-Agent Problem

13 October 2013

No Developer is an Island

People behave with hidden motivations and flawed reasoning.

Let’s look at one of the underlying causes behind why many employees, teams, and companies don’t behave the way we want: the principal-agent problem.

I win even when you lose

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it” - Upton Sinclair

The principal-agent problem arises when the person/group asking for help (the principal) has different incentives from the person/group offering help (the agent). It is even more common in situations where the agent has more expertise, such as a hired professional or specialist.

The reason is that behavior, both individual and collective, changes to follow incentives. Individual will, morality, ethics, and integrity are all altered by circumstance and incentives. The principal-agent problem is already part of your life:

- DBAs are rewarded when they keep production stable, even if it means delaying needed features.

- Developers are rewarded when they ship features, even if it makes an existing application/system less stable.

- PMs are rewarded for being ‘more visible’ or ‘done early’, even if the product is not what customers want.

- School administrators are rewarded for better test scores, even if their students are less prepared to be citizens, innovators, adults

Going further, you find examples of the principal-agent problem leading to control fraud:

I win because you lose

- Bankers are rewarded when they fleece their customers instead of helping them.

- Real-estate agents earn more when they sell a more expensive house, even if it’s more than the buyer can afford.

- Salespeople earn bonuses when they promise features that don’t exist, infuriating customers and their product teams.

- Marketers undercut peoples’ confidence, making them emotionally vulnerable and easier to sell to.

- Universities build fancy buildings, dorms and stadiums to be more ‘prestigious’, and then raise tuition and increase student debt.

- The US Congress creating laws benefiting lobbyists more than their own constituents. The principal-agent problem is a structural problem that contributes to corruption, dead businesses, and bloated institutions.

It is so pervasive that economics majors study its theory. I see the principal-agent problem as a force to be fought and minimized. We each have great potential to change our situation and the world around us, especially if we work hard and think carefully.

Context Is King

“Know your enemy and know yourself and you can fight a hundred battles without disaster” - Sun Tzu

To solve a problem you must know your options. To know your options you must know the context.

- People are authentic, and sympathetic. Companies are not.

- The downside to good customer service is fixed (fixing a person’s problem). The downside to bad publicity is potentially immense.

- Principals, often individuals, have little power or money on their own. Collectively, they control the fate of agents, and thus have immense leverage.

- Legal recourse is often ruinously expensive and full of fine print and loopholes that favor agents.

- Agents remove value from their products/services by adding complexity: loopholes, bureaucracy, and fees. It tilts the information-asymmetry problem in their favor.

- Monopoly companies are exceptionally bad: the barriers to change are so much higher. It is hard to fight ISPs, governments, and utility companies because sympathetic people can’t vote with their feet.

- “Policies” are a bland term that mean “some middle manager decided not to do X because it’s in our best interests”

1. Fight with Data

“The best revenge is to not be like your enemy.” - Marcus Aurelius

You can fight the principal-agent problem with data. Since it often involves information asymmetry , having more information is empowering.

We do this ourselves; it is why popular sites have feedback systems: Yelp, TripAdvisor, Zillow and Amazon.

A powerful way to use data is comparison shopping. We have options to acquire goods & services, and vote with our wallets. Doing so in an informed way helps you choose a superior product/service and support companies whose practices you like.

Luckily for principals, the amount of data and number of skilled analysts are increasing rapidly. However, the vast majority of valuable data is not public. Imagine if detailed insurance company data was public: customers would rapidly switch to the most customer-friendly companies. Companies seeking to maximize profit will hide critical data. Therefore we must get information from unconventional sources or public institutions.

Health Care

A brilliant report by Stephen Brill found that the medical costs are insane. This has been corroborated by many other independent journalists and bloggers. Drug makers make deals to prevent generic (i.e. cheaper) versions of their drugs. It’s sometimes cheaper to pay cash. Visitors from other countries are often appalled by our health care system.

It is easy to skew numbers and hide inefficiency when data isn’t available. Conversely, it’s easy to make systems more efficient when data is available. I’m a big fan of startups that are working on this problem, like Castlight. However, even then the data is not really public.

Data is potentially powerful, and therefore potentially risky. Any individual, group or company with sufficient skill can use data for their own ends. This can be for good reasons, like making health care affordable for the average person, or for nefarious reasons, like figuring out who is more likely to have health issues, so they can be discriminated against (ahem, “priced appropriately”).

Any effort to expose, assemble, or publicize data should involve thought about how it can be used for good or evil. Powerful organizations can handle the risk of embarrassing disclosure. Individuals can’t.

2. Fight with Publicity

One of the big changes in the past decade is the rise of social networking. Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, YouTube and Reddit enable a single person to tell their story and have that story visible to the entire world. Amazon, Yelp, and eBay and other sites enable a person to write a review that can influence many future purchases.

Publicity works because of human psychology. We are a social, tribal species. We are identify with people who seem like us. We love the underdog. Sympathy is powerful.

I’ve never met a company or PR agent that is as sympathetic as a normal person. Companies in general, and PR agents in particular, aren’t authentic. Much of that is cultural; the language that agents use is framed by their worldview (profit, marketing, damage control, shareholder value, etc). I’m glad; it makes fighting the principal-agent problem with publicity really easy.

Publicity works for a second reason: unequal risk. Bad publicity costs far, far more than good customer service does. This is doubly true if an agent lies, argues with their customers, and denies things they have done.

Let’s look at two examples.

Law Enforcement Corruption

Let’s look at when agents have all of the power. Cops can use “asset forfeiture” to seize whatever they want, with low risk of punishment.

Individuals (the principals) in this situation have minimal power. The average person can’t afford lawyers to fight police corruption. However, individuals collectively have massive power; they can vote out the politicians running these towns and states. Even the threat to do so (opinion polls) has tremendous clout.

Lost Baggage

British Airways (BA) lost somebody’s luggage (newsworthy, I know). Unlike an email to the company (easily ignored), that man’s son, @HVSVN bought $1,000 in Twitter ads to publicize his complaint.

Let’s look at what happened:

- Cost to Principal: $1,000

- News articles: 93 (mostly due to novelty)

- Twitter users who ‘engaged’: almost 13,600

- Twitter users who saw the tweet: over 70,000

- 2.5 billion people fly each year

- British Airways flies ~ 57 million people each year

- Q.E.D. : British Airways flies 2.3% of air travelers

Primary Effects

Let’s guess that 1% of the 70K Twitter users were also BA customers, and the average ticket costs around $1000.

- Lost revenue: $700,000

Secondary Effects

Let’s guess that each person knows ~150 people. We can guess the impact:

700 People *

150 People in Network *

50% Chance of Mentioning *

$1000 ticket price

20% are BA customers =

$10.5 million

- Secondary lost revenue: $10.5 million

- Total Lost Revenue: $11.2 million

- Advertising ROI: 11200:1 (1,120,000%)

- British Airways annual revenue: ~$17.3 billion

- Agent:principal income ratio: 302,000:1

- Agent:principal income ratio with advertising ROI: ~1545:1

It’s still not an even playing field. But the odds are better.

The Lesson

Businesses care about money. People care about their jobs. Publicity gives a principal leverage against an agent’s primary weak spot: their wallets.

While researching this post, I found that most successful publicity campaigns had common elements:

- There was evidence. Document everything; use cameras, smartphones, copies of documents, screenshots, Google Glasses, scene re-creations, everything

- An honest, compelling story

- A catchy headline

- Social media. Twitter is great. So are Facebook and Reddit.

3. Fight In Groups

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” - Margaret Mead

The third way to fight the principal-agent problem is with other people. Other people have skills, ideas and connections you don’t. A small team is far more capable than an individual.

The Internet makes organizing far easier than ever before. Anyone can make a site, and anyone else can find it. It’s relatively easy to identify competent professionals and bypass layers of middlemen / bureaucracy.

There are already sites that act as online watering holes and gathering places:

- Groklaw was a clearinghouse for lawyers

- Naked Capitalism is a center for news on financial corruption

- StackExchange/StackOverflow is a gathering place for technical information

- Hacker News is a center for technical news

- Reddit has sub-reddits for every topic imaginable.

- There are Twitter communities for many types of professionals. #SQLFamily, #SQLPeople and #SQLHelp find the SQL Server folks. #rstats finds the data analysis folks.

- GitHub is the go-to place for collaborative development.

Online gathering places are still in their infancy. Here are some examples of what I can’t find:

- Collaborative analysis of legal cases

- A gathering place for medical professionals.

- A gathering place for professors of various disciplines.

- Collaborative development and feedback of political data.

The tools for Internet-based gathering places are largely mature:

- The ability to create and edit information in groups (Google Docs, wikis)

- The ability for people to provide feedback in a productive way (Discourse, reddit’s karma points, StackOverflow’s voting system)

- The ability for people looking for specialized information and collaborators to find them (Google Search)

Let’s look at another area with a bad principal-agent problem: finance.

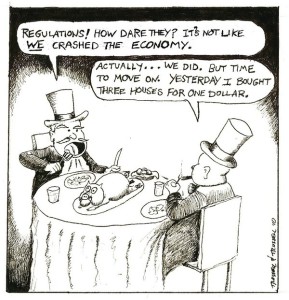

In the US, the financial system is huge and corrupt. Here’s a partial list of what financial institutions have done over the last 10 years:

- commit fraud

- conspire to fund terrorist groups

- bribe (ahem, “give campaign contributions to”) people in power

- siphon funds from your retirement

- pay negative taxes

- Get rid of fiduciary duty

- Add fake fees to mortgages

- “Lose” paperwork to make money

- Foreclosure when they can make a profit

- Foreclose illegally over and over again

- Ignore their obligations as landlords until sued

- Thoroughly capture regulators and rating agencies

- Get appointed to high government positions by both parties

- Stayed out of jail.

- Repeatedly weakened attempts at regulation.

The power and influence that exists in finance comes from the collective money of the average person (i.e. principals). It’s a horrific example of the principle-agent problem.

It’s the Incentives, Stupid

If you can’t fight agents, pick different ones. I’ve found a great alternative to banks: credit unions (which have higher satisfaction ratings than banks).

Financial institutions are vulnerable to customers moving their money somewhere else. Their influence comes from our checking accounts, credit cards, loans, and 401Ks. Move it, and you end up with better service and less organizational corruption. Win win. One recent effort has been the Move Your Money project.

Let’s look at why credit unions are better for customers than banks.

People behave according to incentives. Moral courage is admirable, and rare. Incentives encourage what they measure, and care must be taken to avoid unintended consequences.

Here are my questions to identify incentives when choosing an agent:

- Can the company (agent) make more money by providing bad/no customer service?

- Does the company/agent pay their employees well? If they’re not willing to pay their employees well, how will they treat their customers?

- Are the executives given pay raises & bonuses when the company loses money or market share?

- Do customers influence the hiring/firing of executives? How is bad behavior prevented?

- Is there effective oversight? Does the industry try to capture regulators?

- Is there an incentive for an agent to sell me something I don’t want or need? (e.g. real estate agents, the entire wedding industry)

- What are the industry’s success metrics? How can they be twisted?

- Does the company try and produce more profit each quarter as a percentage of revenue? How do they do that and maintain quality?

- Have other people had a bad experience? How bad? What has been done to provide reparations?

- How easy is it to move to a different agent? How many other options are there?

- How many of the company’s press releases mention “focus on the bottom line”, “maximizing shareholder value”, “profit”, “delighting customers” and other misleading phrases?

- Can I create custom incentives? Some great examples are deferred compensation, flat fees, and profit-sharing arrangements.

When looking at banks and credit unions, incentives are the big difference. Banks are designed to take money from their customers, as profit. The customers aren’t owners. In contrast, credit unions have aligned incentives. They’re nonprofits. The customers are owners. Plus, customers can vote to fire the the board of directors and top executives.

Here are types of organizations with good incentives:

- Health care co-ops (instead of for-profit insurers and hospitals)

- Employee-owned companies

- Cooperative federations

- Mutual insurance companies vs. for-profit insurance companies.

- Public-facing government services (e.g. libraries, firefighters, and public transportation)

Now What?

We are all principals and agents. As principals, we want the best service for the price. As agents, we should provide the best service we can.

Since we are more often principals than agents, we should remember tactics to fight the principal agent problem:

- Know the context

- Fight with data

- Fight with publicity

- Fight with others

- Look at the incentives

Good luck!

Permalink