Leaving the UW

10 May 2018

It has been six months since I left my job as a data scientist at the University of Washington. I joined the UW in 2012 with the personal goal of helping students graduate with less debt. I (naively) thought this would be possible by making a university more efficient. If students can graduate faster, if the right courses have more space, if UW funds are spent more intelligently, then everyone would benefit.

I spent 5.5 years doing this, over 3 of them as the UW data scientist studying student behavior. During that I built dozens of tools to help the UW run more efficiently, such as:

Tools to Help Students

- Identify which students are trying to get into competitive degree programs and aren’t likely to be admitted. Identify and encourage alternate majors as ‘backups’, and the best set of courses to prepare them for any backups they’re interested in.

- Find the fastest and cheapest ways to graduate from every single degree. For example, in Computer Science, there was over 2 quarters’ worth of difference between different course ‘sequences’. Make that information available to students.

- Show a student their personal fastest and/or cheapest way to graduate.

- Identify the AP/IB tests and community college classes that help prospective students graduate faster. Let them tailor the information for the career goals. Make this information publicly available.

- Identify which classes make or break a student’s interest in a degree. Again, make that information public.

Tools to Help Faculty/Staff

- Identify which students will leave the UW in the next 30-90 days, and their risk factors. Make this available to the appropriate advisors/faculty so they can proactively communicate and help retain struggling students.

- Identify which courses fill up quickly, many of which have far more students interested than available space. Expose this information to academic departments so they can help their students. Expose it to students so they can plan for course-registration headaches.

- Identify buildings and classrooms that are not used much. Build a course allocation system so a department can find ‘nearby’ rooms/labs for their classes, and other departments can ‘rent out’ their spare classroom space.. In the long run, this could save hundreds of millions of dollars in construction costs.

- Shows instructors the basic composition of the students in each class: the most common previous courses taken, typical GPA ranges, which other courses are being taken concurrently, the current/likely degree programs for their students.

- Show academic advisors which classes their students need to take to graduate, along with an estimated time-to-graduate for every person they counsel.

None of these ever saw the light of day. To my chagrin and horror, I realized there were no incentives for most staff/faculty to help students graduate with less debt, to help their department run efficiently, or to make bold/risky decisions.

Looking back, my work was doomed to fail, and I was blinded by hope, and didn’t see the clues:

- I never read or heard the phrase ‘student debt’ by anyone employed full time at the UW. Not even once.

- Doing machine learning and stats on student data, the terms I heard most were “enterprise” and “politics around funding”.

- No one was willing to try anything new without scientific proof that it would work. Usually not even then.

- I told a well-connected Vice Provost how to save hundreds of millions of dollars by not building buildings. I was quickly told to drop the subject.

- The most common questions I heard to any suggestion were “what will this do to our budget?” and “what if I lose my job over this?”.

Eventually I realized that my efforts were not helping students, and they never would. If I wanted to change the UW to help its students, its faculty, and its research, I would need to make organizational & political changes, not technical ones. That’s a job for a different person.

So, I left for a different job, with the same motivation as in 2012: to make the world more equitable and just.

PermalinkBuying a Van Using Data

08 June 2017

Two of my most popular posts have been about the unpleasant process of buying a car, including a replacement vehicle, and a cheap car for my sister’s family.

Recently I have been playing music (hauling instruments), and camping (hauling gear) quite a bit. A second car would have been useful. My wife and I decided it was time to get one, and the practical choice was a minivan.

My goal: to buy a minivan that was the best possible value for the money.

Context is King

A vehicle is the 2nd largest purchase most folks make; I could save a lot of money by learning about the auto market and car reliability. I thought about this in terms of costs and benefits.

Costs

The biggest expense of a minivan is depreciation: the difference between your purchase price, and your eventual sale price. That’s likely to be more expensive than gas, insurance, or repairs.

Right now, cars are overpriced for the same reason houses were in 2007: too many loans. Incentives offered by automakers are sky high, and the resulting auto loan bubble may be bursting, even for used cars.

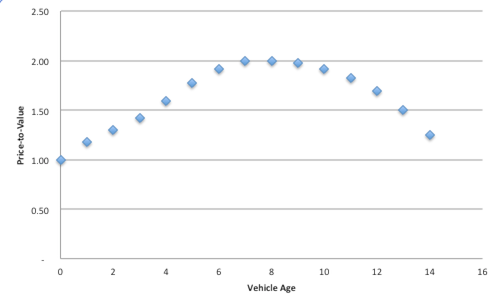

The price of a car drops 15-25% each year for the first five years. Many cars last 200K miles, or about 17 years at the common 12K-miles-a-year pace. New cars are a bad deal.

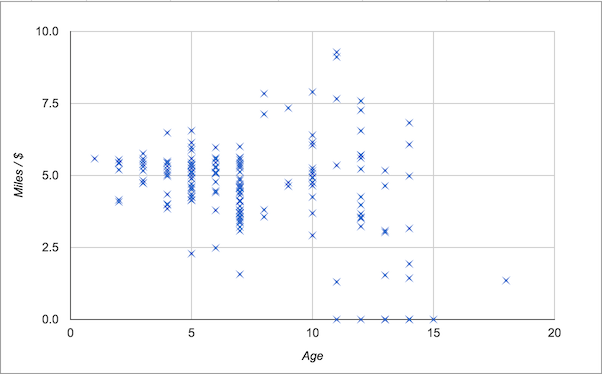

Let’s assume cars depreciate 20% a year for ~5 years, and depreciate 10% a year after that. A well-maintained car is as useful on its 10th year as its first, so we end up with this price-to-utility graph:

Assuming a vehicle will last ~17 years, the best deals are between the 6th and 10th years, the ‘middle third’ of its life.

My goal was now more refined: buy a used minivan that’s the best value for the money, one that is likely 6-10 years old.

Benefits

The benefit of a van for me was obvious: it hauls people, and stuff around. I am not sentimental; a car is a metal box that moves, and fancy features are worth nothing to me.

Goals and Metrics

The cost of a car is money. The benefit is the number of miles it will go before it dies. Ratios are great way to quantify value. In this case, I was looking for Benefit / Cost, or Miles Remaining / Price.

The metric I cared about was Miles Remaining Per Dollar (miles/$). The larger the number, the better the deal.

Not all cars are created equal. Even in the same vehicle segment (minivans), the available choices would differ in price, features, and reliability.

In the past I have had to rely on a composite of opinions about vehicle reliability, because good data wasn’t available. This time was different; I had a quality data source, Dashboard Light.

I used this to compare different minivan models. I could use this data and math to cut through all marketing BS.

Make and Model

I started comparisons with a baseline, a ‘quick and easy’ way to do something. In this case, that was looking for a ‘certified’ used version of the most reliable minivan, a Toyota Sienna. The certification gave it a warranty and assurance it was in good repair.

30 seconds of searching found a $22K certified van would last ~143K miles, a.k.a. 6.5 miles-per-dollar.

That was the baseline: 6.5 miles/$

I looked at other minivans:

- Chrysler Pacifica. ~115K miles for $30K. I guessed this would last as long as the last Chrysler minivan. That meant 3.8 miles/$.

- Kia Sedona. 70K miles left for $17K, meaning 4.1 miles/$

- Nissan Quest. 78.5K miles left for $18K, meaning 4.4 miles/$

- Honda Odyssey. ~113K miles left for $25K, meaning 4.5 miles/$

- Mazda 5. 68.5K miles left for $13K, meaning 5.3 miles/$

- Dodge Caravan. 99K miles for $14.5K, meaning 6.8 miles/$

Going strictly by the numbers, the Dodge van was the best deal. However, other data sources kept reporting Dodge vehicles needing expensive repairs as they aged, so I stuck with the reliable choice.

My goal was now clear: buy a used Toyota Sienna that’s the best value for the money.

The Search

Finding a good deal on a used car was like looking for a needle in a haystack.

There were a lot of options, including TrueCar, Craigslist, AutoTrader, and more.

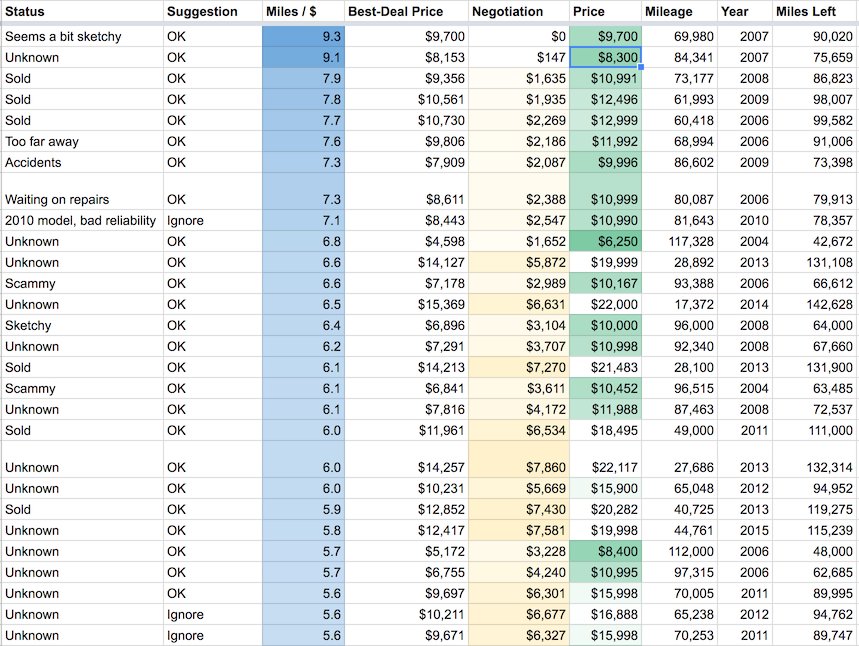

I wanted to be lazy when searching for a car, so I wrote the math into a Google Spreadsheet, and added every Toyota Sienna for sale within 200 miles of Seattle that had less than 160K miles.

After updating this spreadsheet for a week, I ran a quick check. What age of vehicle should I be expecting to purchase? What price range should I expect to pay?

The best deals were between 7 and 13 years old, meaning they were 2004 to 2010 model year vehicles. There were also many used cars that were a worse deal than the baseline; many were wildly overpriced.

The best deals were between $6K and $15K, with most right above $10K.

With this spreadsheet, I could find that elusive needle, by using math to burn down the haystack.

It was time to find and buy a specific minivan.

The Shady Dealer

The best deal when I started was at an official Toyota dealer, Toyota of Bellevue. It was a 2006 van with 93K miles for $10.2K, meaning it had a miles / $ value of 6.6. That was slightly better than our baseline of 6.5. It also had a clean Carfax.

I went out, took the vehicle for a test drive, and it drove well. I negotiated the sales guy down a few hundred dollars for good measure.

It was extremely helpful to have a list of other deals on a Google sheet, because I could pull it up on my phone during negotiations. It’s hard for a salesman to say, “You’ll never find a deal this good” when I can point to 4 other current listings that are almost as good.

Another useful metric, “Best Deal Price”, showed how the maximum to offer for a vehicle and still have it be the best deal available. This was useful during negotiations.

However, I ran into a catch: the manager refused to allow the vehicle to be inspected by an independent mechanic. Refusing to allow a potential customer to pay for an inspection (in this case, an 11-year-old van) is shady as hell.

The sales folks had lots of ‘reasons’, which boiled down to “trust us because we’re big, and we sell lots of cars”.

I had read in many places to never to buy a car without an independent inspection, so I walked away. Afterwards I kept receiving phone calls & text messages from pushy salesmen, who suggested I was being paranoid.

Lesson: Even the big dealers can be unreasonable or scam-y. Considering the money involved, never trust the seller.

Gone in a Flash

For the next 5 days, I called listing after listing, and encountered the same result: the vans had been sold. Good deals (7 miles / $ and higher) sold within a day or two.

I had to change my strategy. I couldn’t search in the evening and call in the morning; I had to check multiple times a day, and call immediately after finding a good deal.

The Fast Deal

I found my next good deal several days later, at Rich’s Car Corner, a nearby used-car dealership.

The vehicle was a 2007 Sienna with 84K miles for $8500. In other words, a value of 8.9 miles/$. It was the best deal yet.

An AutoCheck history showed the vehicle had one accident 8 years ago, and had been well-maintained since. That was promising, so I went to the dealership, where there were a few promising signs:

- The sales guy was willing to let me “test drive” the vehicle for several hours.

- An independent mechanics’ inspection found nothing major wrong, and gave me an estimate for $700 in small repairs (badly worn brakes, smoky transmission fluid, low steering fluid).

The value was then 8.2 miles/$. That was still the best deal I’d found.

Now came the trickiest part: negotiation. I knew I had a great deal available, using information the dealer didn’t have. That gave me an edge. I was able to negotiate the price down to $8000, arguing that it was an old van that needed hundreds of dollars of repairs.

A Bad Taste

Finally came the challenge I wasn’t prepared for: paperwork scams. The dealer had a pretty bad reputation for selling junkers, but it turns out they also tried to make money in other ways:

- Fake fees

- Double-counting fees

- ‘As is’ purchase agreements

- Lying about time requirements to complete car registrations and do a title transfer

Worst of all was an ultimatum: sign an arbitration agreement, “or else we can’t legally transfer the title to you”. Talking around that one was the last hurdle.

The purchase process complete, I had my new van, and a bad taste in my mouth.

The Unexpected

I took the van to my favorite mechanic, who came back with bad news. The earlier mechanic had missed that the leaks were symptoms of larger issues. The van needed new front suspension, steering racks, front brakes, and alignment. The repairs cost $3000, so I ended up spending $11000.

After all that, I had purchased a minivan with a value of 6.9 miles / $.

Epilogue, Lessons Learned

Look

Purchasing a vehicle in a data-driven way was an interative process:

- Find a minivan

- Find a minivan that was 6-10 years old

- Find a 6-10 year old Toyota Sienna minivan

- Find a 6-10 year old Toyota Sienna with a value better than 6.5 miles / $

Duck

I was able to avoid several traps by knowing they existed, and ways around them:

| Trap | Tactic |

|---|---|

| Dealers will pressure you; they have quotas to meet | Be prepared to walk away from a bad deal |

| Dealers are more desperate near the end of the month/quarter | Go then, and bargain harder for a deal. You have leverage then |

| Auto loans are a pain, and sometimes predatory for minorities | Save up, and pay in cash |

| Auto loans aren’t available for older (cheaper) cars | Save up, and pay in cash |

| The dealers near you don’t have the best deal | Search widely. Driving 200 miles to buy a car is a cheap way to save \(\) |

| Fancy features are expensive | Buy them later, if you still want them |

Weave

Along the way came several interesting lessons:

- Dos research first. Good data and a little math is a large advantage when searching for a vehicle.

- Dealer reputation doesn’t matter. Shiny places can be shifty. Old shops can have great deals. Trust no one, and verify everything.

- Always be ready to walk away.

- Check for open recalls. Never buy anything that isn’t fixed first.

- Don’t buy somewhere sketchy

- Take a tape recorder with you, and get all the negotiations and paperwork recorded. If I’d had a recording of that arbitration threat, I’d have gone to the state Attorney General’s office with it. Somebody should protect future customers from the same scam.

- This approach wouldn’t work for most people; far too many people are poor

I’m going to wrap up this long-winded post with one of my favorite quotes:

“At the heart of science is an essential balance between two seemingly contradictory attitudes-an openness to new ideas, no matter how bizarre or counterintuitive they may be, and the most ruthless skeptical scrutiny of all ideas, old and new. This is how deep truths are winnowed from deep nonsense.” - Carl Sagan

Permalink