2015, Unfinished

30 December 2015

2015 is at an end. Each year I think on the events and patterns of the year, as a reflective practice. I grow and learn more when I use hindsight to my advantage.

Let’s start with the projects and work I didn’t do. I don’t have regrets, but I don’t if I would make the same choices, either.

Learn

As an aspiring polymath, I am always learning something new (and forgetting something old; cache eviction happens to humans too). Sadly, I was not able to learn a few things I aspired to:

- JavaScript and React.js

- Scala, in more depth

- C / C++

- Bayesian inference

Lesson: I didn’t devote significant time to these things. I didn’t even start learning most of them. I always felt I had something more important to do. So the real question is whether my sense of judgment is wise, day-to-day.

Understand

When I’m not spending time at work doing data science, I’m doing it at home, on side projects. My life is awesome that way.

- An analysis of fruits, vegetables and pesticide risks. The FDA shows which pesticides are present in what produce, but not the amount or the relative risk of those pesticides. What are the relative risks of different kinds of produce? Is buying organic safer? If so, how much?

- An analysis of California’s water supply and water usage problems. Why do farmers grow rice, or cotton, in an arid climate?

- Another analysis of car value. Can we predict the cost-per-mile to own any used car?

- An analysis of health costs

- An analysis of higher education choices to help students pick a college using data.

- An analysis of whether the upcoming merger of Group Health Cooperative and Kaiser Permanente will result in higher health-care costs for patients.

- An analysis of brilliant, productive people, and any unusual traits or habits. In particular, what do incredible people do that is statistically different from the average person?

Lesson: These projects didn’t get far because I didn’t have the time/inclination to pursue them over other ideas. Several of them, notably around health-care and people’s behavior, are limited by a lack of data that’s easily accessible.

Communicate

I didn’t update my blog much; I was usually chatting with on Twitter. I did maintain draft blog posts, mostly as a personal knowledgebase.

- A post on good privacy and security advice

- A multi-part post on ethical choices for software engineers, data scientists and others

- A post on the wisest lessons I’ve learned about software engineering, including software engineering as a craft

- A post on the wisest lessons I’ve learned about job searches

- A post on the wisest lessons I’ve learned about data analysis, machine learning, statistics, and data science and feature engineering.

- A post on the value of the precautionary principle and systems thinking

- A post on the value of playing music as a way to keep learning, forever

- A post on using curiosity as a way to learn more without having your confidence/ego threatened

- A post on thinking of life as a linear optimization problem

- A post about project planning methods and approaches.

Lesson: This year I was more intentional about communication, and focused on back-and-forth communication (Twitter) rather than one-way communication (a blog).

Reflect

A few lessons and changes are apparent from this year.

- For analysis projects, make sure I care enough to start one. Use cleaned-up / available data sets when possible

- Be intentional with larger-scale projects and efforts. There isn’t time to do very many of them.

- For everything else, go for incremental improvement over what others have done.

- Change the format of my blog to be more collaborative. Hosting IPython notebooks would be a great start.

Show Me the Tuition

23 July 2015

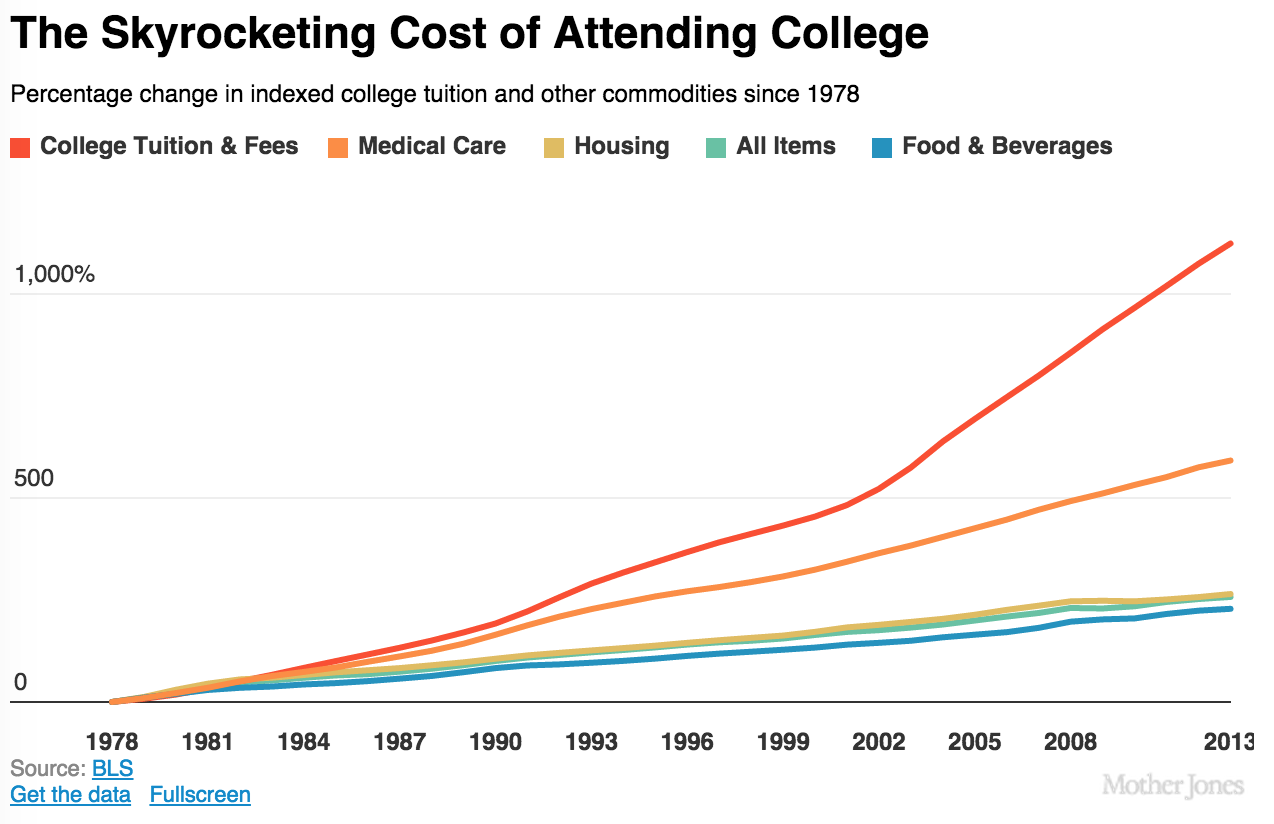

College in the United States is expensive.

For all of the news about tuition increases and state cutbacks, there’s very little media coverage about how universities spend their money.

One of the best college systems in the U.S. is the University of California (“UC”) system. However, recent tuition increases are so painful they’ve led to student protests, and revealed outright contempt of students by UC leadership. Where does its money go?

The Data

The UC spends over two-thirds of its funding on staff. The rest goes to large expenses (buildings), financing (paying off debt), and miscellaneous expenses. However, those are related to the number of employees; buildings exist because people work in them.

The University of California’s official budget website does not provide a useful breakdown further than that some high-level numbers. However, the State of California does provide the amounts it pays to its employees by title, along with the number of employees in each role. Thank goodness for public data.

After cleaning up the raw public data and coming up with a cleaner data set, I was ready to do analysis.

Warning: this data is not 100% correct, because I have had to guess what some job title acronyms mean. It is largely accurate.

Show Me the Money

Most of the university’s expenses are for administration and medicine.

Only ~30% of the UC’s budget goes to teaching. Of that, almost half goes to medicine. Non-medical teaching, including professors and TAs, is only about 15% of salary costs.

Most university revenue, like student loans, doesn’t go to teachers. It goes to the huge teaching hospital and administrators in office buildings. Sure, patient fees and grants make up for a lot of that, but it’s clear that all non-teaching activities are the tail that wags the dog.

What is the UC System?

The University of California system is a collection of medical centers and large administrative staff. The teachers and researchers are there as window dressing.

Medicine vs. Not

Medicine is a huge amount of the money being spent by the UC system.

Administration vs. Not

It’s not a majority, again, but it is quite a bit.

Academic vs. Not

Most of the money doesn’t go to academics. The University of California’s own data supports this.

Give examples of titles for each category.

It’s About the Incentives

I think I can see why salaries are allocated this way: the incentives are messed up.

Administrators have no incentive to cut their own budgets, their staff, or their authority. They’d be less important, and be able to offer less ‘comprehensive’ ‘solutions’ to (Insert Issue Here) if they did.

I’ve lost count of times I’ve heard the gnashing of teeth that some college lost a couple of places and ‘prestige’ in the U.S. World & News Report, and hired administrative staff to make things better.

Colleges are focusing heavily on increasing scope and adding control, which increases costs. Anyone who has ever heard of the Iron Triangle could tell you this was going to happen.

Implications

The implications are profoundly positive. It is possible to make universities cheaper and improve the lives of faculty. There are some important but systemic changes that could be made:

- Cap the administrator:student ratio to a level seen in the 60s, 70s or 80s. Fire some administrators.

- If tuition goes up, all high-level administrators should automatically take a pay cut equivalent to the tuition rate increase.

- Appoint a university ombudsman specifically tasked at making their teaching hospitals more cost-efficient.

What has been tried so far is not working. It’s insane to do “the same thing over and over and expect different results” (Einstein).

Permalink